The Hermit’s Paradox: How Solitude Reveals Life’s True Meaning

Discover the surprising wisdom of a British army officer turned Buddhist monk who found enlightenment—and a tragic end—in a remote Sri Lankan jungle.

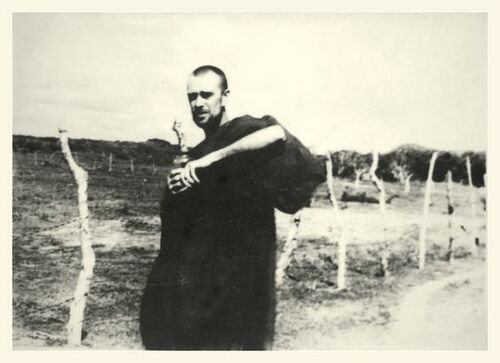

Nanavira Thera’s life, a whirlwind of espionage, hedonism, and ultimately, profound spiritual seeking, offers a potent metaphor for navigating the complexities of existence. His story, recounted in Robin Maugham’s “The Hermit of Bundala,” isn’t simply a tale of a man seeking refuge; it’s a radical exploration of what it means to confront the “problem of existence” – the inherent suffering and uncertainty at the heart of human life. Born into privilege and trained for war, Harold Musson’s journey took a dramatic turn after a chance encounter with Buddhist teachings. Inspired by Evola’s “The Doctrine of Awakening,” he abandoned his former life and joined a small monastic community in Sri Lanka, seeking a path beyond the distractions of the material world.

The Bundala National Park, a place of both beauty and danger, became his hermitage – a deliberate isolation designed to strip away the layers of ego and societal conditioning. He wasn’t seeking a passive, meditative state; rather, he aimed to engage directly with the Buddha’s teachings, recognizing that true understanding could only arise from confronting the uncomfortable truths about oneself. This approach, deeply influenced by existentialist thinkers like Kierkegaard and Sartre, involved a willingness to grapple with anguish, anxiety, and the inherent absurdity of life. Nanavira’s decision to live as a hermit wasn’t merely a retreat; it was an active choice to resist the seductive pull of distraction and to embrace the “issue” of his own existence.

His biography reveals a fascinating paradox: while physically isolated, his mind was intensely engaged with philosophical inquiry. He meticulously translated Buddhist texts, corresponded with scholars, and wrestled with complex ideas, producing a substantial body of work. Yet, he also struggled with debilitating physical ailments – intestinal disorders and satyriasis – which ultimately led to his tragic suicide in 1965. His final act, a deliberate release of ethyl chloride, was a testament to his commitment to his chosen path, a final assertion of control over his own destiny in the face of overwhelming suffering.

Nanavira’s story isn’t about finding easy answers or escaping the world; it’s about confronting its challenges with unflinching honesty and a radical commitment to self-awareness. His life serves as a powerful reminder that true freedom lies not in seeking external pleasures or avoiding discomfort, but in embracing the “problem of existence” and dissolving the illusion of a fixed, separate self. Like the hermit of Bundala, we too can find solace and meaning by turning inward, confronting our own anxieties, and recognizing the interconnectedness of all things. His legacy continues to resonate today, inspiring those who seek a path beyond the superficiality of modern life and a deeper understanding of the human condition.

David E. Cooper: The Rhetoric of RefugeThe rhetoric or metaphor of refuge has largely disappeared from religious, social and ethical debate. The contrast with the past is striking.

Some people will judge that he paid an excessively high price for his commitment. Had he disrobed and returned to England, he might well have been cured of his amebiasis, colitis and satyriasis and not taken his life.But this is not how Nanavira could have judged the situation. In a letter written the year before his death, Nanavira explains that his illness could not be ‘allowed to have its own way’, and that disrobing was only justified if a monk had disgraced the monastic order. As for returning to England, he joked that he couldn’t live on a diet of bread and potatoes, but added, more seriously, that when he left England he’d counted himself fortunate, even if he were able to practise the Dhamma for only a single year. His sense of estrangement from European civilisation was total. The letter ends, with characteristic humour, by asking if he should ‘abbreviate the process’ of his life, even if ‘the age of forty-four is rather early to close the account’. Nanavira’s decision, some months later, to close this account is not one, he would insist, for others to question. In the terminology of Being and Time, the book he put down on the day of his suicide, no decision can be more ‘ownmost’.ReadingNanavira Thera, Clearing the Path (1960-1965), Path Press Publications, 2010. [This volume includes Notes on Dhamma and many letters].Bhikkhu Hiriko, The Hermit of Bundala: Biography of Nanavira Thera and reflections on his life and work, Path Press Publications, 2019.Stephen Batchelor, ‘Looking for Nanavira’, in his Secular Buddhism: Imagining the Dhamma in an Uncertain World, Yale University Press, 2017.◊ ◊ ◊David E. Cooper is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Durham University, UK. He has been a visiting professor in several countries, including the USA, Canada, Malta, Germany and Sri Lanka. He has been the Chair or President of a number of academic societies, including The Aristotelian Society and The Nietzsche Society of Great Britain. His many books include World Philosophies: An Historical Introduction, The Measure of Things: Humanism, Humility and Mystery, A Philosophy of Gardens, Animals and Misanthropy, and Pessimism, Quietism and Refuge in Nature. He is also the author of three novels set in Sri Lanka.David E. Cooper on Daily Philosophy:Huts, Homelessness and Heimat. Chōmei and HeideggerJeremy Bentham on Animal Ethics. Philosophy in QuotesShort storyHappinessHermitsHistoryInspirationWisdom seekersAsian philosophy

Keywords: Nanavira Thera, Buddhism, Hermitage, Existentialism, Philosophy, Sri Lanka, Suicide, Solitude, Suffering, Meaning, Self-Awareness, David E. Cooper, Refuge, Being and Time.

No Comments