The Enduring Blade: Flowing Through Life’s Toughest Challenges

How a 2,000-year-old story about a cook, an ox, and a knife teaches us the art of effortless problem-solving.

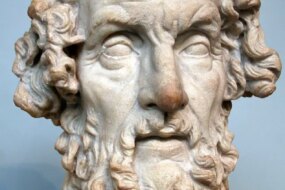

Ancient wisdom often hides in the most unexpected places. In the 4th-century BCE text The Cicada and the Bird, Christopher Tricker translates a profound parable from the philosopher Chuang Tzu. It is a story about a cook carving an ox for a Cultured Benevolent Lord, a scene that elevates a grimy kitchen task into a sacred dance.

The narrative describes a knife that remained sharp for nineteen years. The secret? The cook, unlike common butchers who hack at the meat, seeks the spaces between the joints. By feeling the natural grain of the ox rather than imposing his will, his blade never dulls. This is a metaphor for navigating the “oxen” of our lives—the complex situations and problems we face.

Chuang Tzu suggests that we often approach difficulties with “administrative thinking”—rigid labels and agendas that hack away at resistance, leading to burnout and a “dulled knife.” Instead, the Taoist path invites us to suspend our mental constructs. When we stop identifying with our egos and agendas, we enter a state of egoless awareness. We see the gaps in a problem, the natural seams where things can unravel without force.

This doesn’t mean passivity. It requires a slowing down, a “daemon’s longing” that yields to the situation’s structure. When we trust the process, the “knot” of a problem often falls apart on its own. An unravelled situation, much like the ox, nourishes the whole of life. By embracing the “useless” philosophy of yielding, we find that the edge of our vitality remains keen, capable of carving through decades of challenges without wear.

No Comments