Why Counterfactual Thinking Misleads Us About the Past and Our Future

Ever wondered if a single choice could rewrite history? Counterfactuals promise that, but the truth is far more nuanced.

Counterfactuals—those “what if” scenarios that pop up in novels, history books, and our own regrets—are tempting because they offer a simple narrative: if only I had acted differently, the outcome would have been better. Yet this illusion hides a web of hidden variables and contextual forces that make the imagined alternative far less likely than it feels.

1. The Hidden Cost of “If Only”

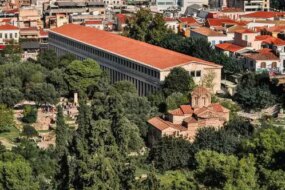

When we say, “I should have not drunk last night,” we ignore the stress, habits, and social cues that led to that decision. Historians point to Neville Chamberlain’s 1938 Munich conference: he wasn’t simply choosing between appeasement and confrontation; he weighed Britain’s unpreparedness, the memory of World War I, and the political climate. A single decision point rarely exists in isolation; it is the product of a complex environment.

2. We Favor the Desired Outcome

Our counterfactuals are colored by what we want to see. The myth that a firm stand at Munich would have forced Hitler to back down fuels modern foreign‑policy rhetoric, even though scholars like Yuen‑Foon Khong argue that a confrontation could have sparked internal German conflict or even accelerated war. The lesson we draw—“confront aggression”—reflects our present values more than any historical certainty.

3. Counterfactuals Reveal Dissatisfaction, Not Destiny

The urge to imagine a better past often signals current discontent. Just as a historian might ask, “What if Britain had stood up to Hitler?” a person might ask, “What if I hadn’t argued with my colleague?” Both questions stem from a sense that the present is unsatisfactory. Recognizing this emotional driver helps us shift from blame to proactive change.

4. Use Counterfactuals as a Tool, Not a Verdict

Instead of lamenting missed opportunities, treat counterfactuals as a diagnostic exercise. Ask: “What conditions would have needed to change for this alternative to be plausible?” This reframes the scenario from a simple “if” to a realistic set of variables we can influence—stress management, communication skills, or broader systemic support.

5. Focus on Actionable Futures

The real power lies in translating insight into behavior. If you recognize that stress triggers drinking, you can experiment with meditation, exercise, or therapy. If you see that a lack of preparedness shaped Chamberlain’s choice, you can advocate for stronger defense or diplomatic readiness today.

In the end, counterfactuals remind us that history—and our lives—are not a series of inevitable outcomes but a tapestry woven from countless decisions and contexts. By acknowledging the complexity behind each “what if,” we free ourselves from the paralysis of regret and open the door to intentional, informed action. Your time spent reflecting on the past can become a catalyst for a more deliberate future.

No Comments