Freud’s Enduring Wisdom: Work, Love, and the Reality of Dreams

Freud’s psychoanalysis is often seen as clinical, but it’s actually a philosophy for living—grounded in wish-fulfillment, Socratic humility, and navigating the tensions between instinct and civilization.

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, held a complex relationship with philosophy. While both disciplines seek to explain the world, Freud turned that explanation inward. He wasn’t interested in detached speculation; he wanted tools to navigate the conflicts of daily life. By grounding his theories in the hard realities of human nature, he bridged the gap between abstract thought and the practical business of living.

Instinct, Culture, and the Liberal State

At the heart of Freud’s worldview is the clash between human instinct and the external world. We are driven by primal urges, but society demands compromise. This friction isn’t a flaw to be eliminated; it’s the engine of civilization. As Francis Bacon argued, reasoning should serve “the relief of man’s estate,” alleviating suffering rather than just pontificating. Freud agreed. He believed true mental health comes from accepting this diminished sphere of action—finding freedom within limits rather than fighting for an impossible total liberty. It’s a uniquely modern ethical system.

The Socratic Analyst

Freud practiced what he preached, much like Socrates. Unlike the aristocratic Plato or Aristotle, Socrates moved through the marketplace of ideas, engaging in dialogue to reveal our collective ignorance. Freud mirrored this in his “talking cure.” He rejected the idea that the philosopher must be aloof from the world; instead, he merged the roles of worker, husband, father, and healer. He understood that right conduct—ethics—is found in the commitments of “work and love.” By building psychoanalysis from nothing, he proved that self-examination could also be a livelihood.

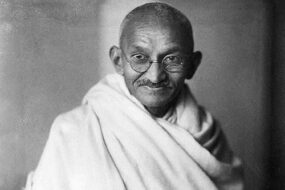

The Dream as a Decipherable Code

Perhaps Freud’s greatest disruption was redefining the dream. Descartes had dismissed dreams as deceptive illusions threatening rational order. Freud rescued them. He argued that a dream is a “wish fulfillment,” a distorted message from the unconscious designed to bypass the censorship of our polite, conscious minds. He turned the dream from a spooky artifact of the divine into a psychological hieroglyph. In doing so, he didn’t destroy reason; he extended it into the darkest corners of the human mind. By decoding these hidden desires, we can understand the forces driving our waking lives.

Discontents and Realism

In his later work, such as Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud adopted a harder realism. He noted that every technological gain brings a loss—telephones connect us across oceans, but often disconnect us from the children in the next room. This isn’t nihilism; it’s the acceptance of universal unhappiness. He famously suggested that the goal of therapy is not bliss, but the transition from acute suffering to “ordinary unhappiness.” Even the controversial Oedipus complex serves this pragmatic purpose: it strips away the romantic illusions of family life to reveal the raw power dynamics and material needs beneath.

The Takeaway

Freud remains essential not because he cured all our ills, but because he gave us a language for our internal conflicts. He taught us that our dreams have meaning, our instincts are powerful, and that a life well-lived requires balancing our deepest desires with the demands of reality. In a world obsessed with optimization, Freud’s insistence on the struggle of work, the complexity of love, and the value of ordinary unhappiness feels more relevant than ever.

No Comments